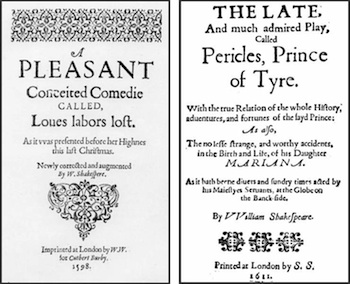

Today I will take on the unsurprising thesis that Love’s Labour’s Lost is a better play than Pericles Prince of Tyre. The very fact that thesis does not surprise us is itself important, since it means we all agree a play about royal heroes, alluring princesses, evil kings, loyal nobles, dastardly assassins, incest, famine, shipwreck, infanticide, pirates, slavery, prostitution, and divine intervention is less exciting than one about some people flirting for two hours to no particular end.

The simple conclusion that it’s a bad idea to pack too much plot into a 20,000 word story (on the short end for a modern novella), but by digging deeper I hope we can look, both at plot, and at the many things which aren’t plot that make up the length of a play or story, and how those other components can make a giant epic spanning five kingdoms and two decades less gripping than Love’s Labour’s Lost, which I choose for comparison because it is not merely a story about nothing, but, in many ways, a story about less than nothing.

Few of us have had the privilege of seeing Pericles Prince of Tyre, because rare is the brave theater company that dares put it on. It isn’t canonical enough to draw crowds like Hamlet or Macbeth, especially since we now agree Shakespeare only wrote the second half, and the rest was probably by one George Wilkins, an inkeeper, pamphleteer, pimp and criminal whom I would call infamous except that infamy requires that people have still heard of you. Pericles is also rarely put on because the staging is tricky, requiring multiple sea voyages as well as multiple kingdoms, which can get expensive or require elaborate lighting tricks and physical acting if a troop can’t manage a full set change for every fleeting scene. And the play requires the protagonist to age twenty years over the course, and nowadays it’s hard to muster the time or funds to do old age makeup good enough to satisfy audiences spoiled by the latex, computers and budgets of Hollywood. We have many more opportunities to see Love’s Labour’s Lost, which not only has some of Shakespeare’s best and most elaborate witty language, but can be performed with a single prop bush. (See also why, even though Thornton Wilder won Pulitzers for both Our Town and Skin of Our Teeth, you will have many more chances in your lifetime to see Our Town. Staging requirements of Our Town: four chairs. Staging requirements for Skin of Our Teeth: furnished suburban home, overhead projector system, dinosaur, woolly mammoth, large glacier which enters and destroys the set.)

But the other enemy of Pericles is its own plot, which is partly the fault of the ancient and medieval sources it is based on, but only partly. I want to pause here to say that I love Pericles Prince of Tyre, and have rushed to see it every chance I get. It’s a rollicking wild ride, and if I say silly or unkind things about it here, it is the kind of affectionate teasing reserved for things we love, and consonant with the fact that these plays are comedies and (despite whatever stuffy 19th century literary critics might say) they’re supposed to be funny.

Let us first compare the plot summaries of our two plays (SPOILER ALERT):

Pericles, the young ruler of the ancient Mediterranean city-state of Tyre (in Lebanon) sails to Antioch, seeking the hand of its famously beautiful princess. Her father has pledged to marry her to whoever solves a difficult riddle, but suitors who fail are executed. Pericles solves the riddle, and its solution reveals that the king and his daughter are committing incest (which would be a great twist if it hadn’t been spoiled by the prologue). Disgusted and afraid of the evil king, Pericles flees, and the evil king sends an assassin to kill him to keep the incest a secret (Cue audience: “If you wanted to keep the incest a secret why did you put it in the riddle in the first place?”) Not daring to return home, Pericles journeys to the (randomly-selected) land of Tarsus, and saves its people from a famine with his huge loads of grain (Why did he have all this grain with him?), earning the eternal gratitude of its king and queen. With the assassin still on his heels, he sets out again but is shipwrecked, and washes up on a beach in the distant land of Pentapolis with nothing but his armor (which is miraculously found by fishermen). By bizarre coincidence, that very day the king is about to celebrate his nubile daughter’s birthday with a joust (What century is this supposed to be again? Something BC?), and the mysterious stranger wins the tournament, the princess’s heart, and, after revealing his noble pedigree, the king’s blessing. Back in Tyre, Pericles has been gone so long that his people try to make his steward become king, but the faithful steward struggles to make them await Pericles’ return. Meanwhile off-stage the evil incestuous king and princess of Antioch are incinerated by lightning. And now that it is safe to return home, Pericles sets sail with his pregnant queen, but she goes into labor during a terrible storm, bearing a daughter named Marina, but dying in the process. Distraught, Pericles lands in Tarsus again, then sails home leaving his infant daughter in Tarsus to be cared for by its king and queen (the eternally grateful ones, from the famine) who have just had a daughter of their own, so will raise the two princesses together. Meanwhile the coffin with the corpse of Pericles’ dead wife washes up in the unrelated and distant land of Ephesus, where she is revived by an impossibly skilled physician. Convinced that she will never find Pericles or her child again, she becomes a priestess of Diana.

Here ends the first half of Pericles Prince of Tyre. I want to pause here to digest. We have met five kingdoms: Tyre, Antioch, Tarsus, Pentapolis and Ephesus. We also have four separate princesses going on, in only an hour’s worth of action. (Think of how many films Disney produced before they even resorted to having two princesses at once!) We have had moral lessons: good people of Tarsus being rescued from famine, the incestuous King and Princess of Antioch incinerated by wrathful gods. And we have had fate’s cruelty/whimsy in the storms and shipwrecks, and the armor and not-quite-dead queen being washed ashore. Taking stock of what plot threads remain: we lost the villainous King of Antioch—who might have been main villain material—and Pericles is safely at home, so our remaining threads are few: the stranded queen, the infant daughter, and the audience’s confidence that our hero Pericles is the type which heavy-handed Fate will continue to throw things at.

Now let’s check out what plot we have in an equivalent first hour of Love’s Labour’s Lost:

King Ferdinand of Navarre vows to spend three years on a course of vaguely-defined “study” while avoiding all contact with women. On the very day that the handsome unmarried king forces his three handsome unmarried courtiers to take this vow along with him, the beautiful unmarried Princess of France turns up with three beautiful unmarried Ladies in Waiting to demand the disputed territory of Aquitaine (a plot thread Shakespeare drops faster than an off-stage incestuous princess can say: “Look, Dad, lightning!”). The ladies already have crushes on these famous gentlemen, and the four men instantly fall in love with the corresponding ladies, all in the correct pairs (no love triangles or hexagons here). But alas!—these men will be oathbreakers if they woo these ladies, so they are wracked by forbidden longing. Meanwhile the ladies tease them mercilessly. After some agonizing and many puns, the king and his three companions all catch each other writing love sonnets, and decide together to break their oaths and woo the four french ladies. (Accompanying these lords and ladies are a Spaniard, a page, a wench, a rustic man, and a witty Frenchman, none of whom has any particular goal beyond flirting. Also around are a constable, a schoolmaster and a parish priest; “they fight crime,” where crime in this kingdom is defined as flirting.)

Pausing at the midpoint, the comparative simplicity is obvious: two kingdoms instead of five, four ladies again but with one straightforward origin, no travel sequences. There is—compared to storm, famine and incest—nothing going on. In fact, there is nothing going on in a literal sense. The only thing that ever stood between our characters and the happy “everyone gets married” comedy ending is the men deciding to avoid women, and the solution is the men changing their minds. There is no villain, no crisis, no impediment, no unrequited love, disguise or mistaken identity, not even a misunderstanding. Nothing is going on. Yet the audience has spent the last hour laughing until we ached.

What just happened?

The answer comes when we outline the plays differently, not in terms of plot, but in terms of the different components which make up the structure of a pre-modern European comedy. And for this we must travel back in time to the classical world (when Pericles is vaguely maybe supposed to be set?). To that end, I present to you one of the leading candidates for “Oldest Joke in the World.”(This is meant to be an interruption, insertable into any scene where a character hears a piece of news, so just pick an arbitrary spot in the most recent book you were reading and imagine this addition.)

A messenger bursts in, and gasps out between panting breaths that he has incredibly important, exciting, amazing, earth-shattering news. The other characters rise in excitement and beg to hear the news. Oh, but the messenger is too breathless! The journey was so long! So hard! Up hill both ways over jagged rocks and blasted heaths—he gasps this out between exaggerated breaths. They ask again: what’s the news? Oh, but he’s too thirsty! Parched from the beating sun, the desert sands, exhausted from scaling mountains, leaping fences, crossing tightropes, wrestling tigers, battling bandits, daring death. They bring him [insert beverage] and he guzzles it loudly and elaborately, spraying it everywhere, demanding a second flagon, a third, panting out more details of his journey—misty mountains, wild horses, wicked viziers—and repeating again how staggeringly, world-changingly, epoch-makingly important this news is. The characters become increasingly annoyed: asking, coaxing, begging, bribing, demanding, shouting, threatening. Mad with frustration they may even attack the messenger, shaking him, dumping a drink over his head, finally tackling him to squeeze the news out, so the whole scene degenerates into wild physical comedy. If the troop is good, the laughter has been side-splitting for at least six minutes before we finally hear the news.

This “messenger gag” is possibly better characterized as a “bit of business” in the stage sense rather than a “joke.” It dates back to the earliest records of classical comedy in Greece and Rome, in which context we call it the “running slave” bit, since in ancient comedy messengers were usually slaves. And it kept being funny for two millennia. Modern audiences are most likely to have seen it in Henry IV part II, when Pistol comes to tell Falstaff that Henry IV is dead, a perfect example because the audience already knows the news, so we are just enjoying watching the torment as Pistol refuses and refuses and refuses to actually deliver the message. A dry performance of the Messenger Gag is dry, but a good one can be the highlight of an Act. It is precisely the sort of comic business which Pericles Prince of Tyre could have had many times (“Prince Pericles, news about the King of Antioch!” “What? What is it?!” “Oh, but I’m so thirsty, I swam all the way from Italy to Troy while fleeing a possessed hippocampus!”). But Pericles didn’t have room for comic bits like this—it was too busy having plot.

Bits of “business”—classic gags like eating in a silly way, or a person in disguise in drag constantly almost getting exposed—are still central in a lot of modern comic scenes, from Monty Python to the movie Willow, but in classical and Renaissance comedy they were even more core. Commedia dell’Arte—in effect the most ubiquitous form of comedy in Shakespeare’s age and a huge influence on his audience as much as on him—relied on stock, improvised bits called lazzi. These would interrupt the plot action with long sequences such as “a character tries and fails to climb a ladder” or “a character in disguise pretends to be a nobleman” or “a character eats noodles” and a veteran improviser could make the act of eating squelchy, squirty, tangly noodles a hilarious one. There are documents reporting one Italian player working in France who supposedly once kept an audience rolling in the isles for twenty minutes with the single lazzo of sitting in a squeaky chair and mistaking its noises for someone sneaking up behind him, so freezing every time it squeaked to try to listen to where the intruder was, thus trapping himself in the chair. Lazzi were sometimes spontaneous additions by the players, but often planned. The scripts that survive for Commedia dell’Arte plays are usually not really scripts in the Shakespearean sense, since they rarely spell out any dialog. Instead they provide a skeleton of events onto which lazzi can be appended, as in this example (translation from Mel Gordon’s Lazzi: The Comic Routines of the Commedia dell’Arte, 1983, p. 51):

PANTALOON says (in a stage whisper) that his creditors, especially Truffaldino, insist on being paid; that the extension of credit expires that day, etc.

TRUFFALDINO (scene of demanding payment).

BRIGHELLA finds a way of getting rid of him.

PANTALOON and BRIGHELLA remain.

TARTAGLIA comes to the window and listens.

BRIGHELLA espies him. He and PANTALOON pretend to be very wealthy.

TARTAGLIA comes down into the street. He goes through the ‘business’ of begging for alms from PANTALOON. In the end they agree to a marriage between TARTAGLIA’s daughter and PANTALOON’s son.

TRUFFALDINO again demands his money.

BRIGHELLA makes believe that PANTALOON gives it to him. He does this three times, and then all three go out.

The script above is all we have for half an Act, not a scene but an entire Act. That means it filled at least a half hour. With the example of the messenger bit in mind, it is easy to envision how a good comedy team can make many laughs (and many minutes) of moments like “scene of demanding payment” or “He and Pantaloon pretend to be very wealthy.” And since these Lazzi are often physical comedy, more non-dialog action than dialog, we know they happened in scripted comedies as well. When Henry IV and Plautus’s Aphitryon do the messenger gag they don’t write down “Messenger arrives winded and strings out the scene with long gasps and funny breathing,” they know the comic troop will recognize the messenger gag and add it.

So, as we have reconstructed them, all stages of classical and Renaissance comedy contained lots of lazzi-like physical and often improvised comedy for which the script was a skeleton and launch pad. This humor is invisible when you read the text plain, and is why the comedies are so much funnier live than read, at least in productions which have escaped the unfortunate 19th century trend of insisting that “high culture” like Shakespeare can’t be funny, and that the clown parts should be read (and performed) as dead serious social commentary. Interruptions for dance, music and song were also (we now believe) common, and Shakespeare’s scripts specify many points at which talk would have stopped for a song, as in the post-joust banquet dance in Pericles or the point in Love’s Labour’s Lost when the love-struck Spaniard asks his page to sing to cheer him up (and modern troops struggle to maintain interest through the repetitive song in French, in an age of recorded music, when the audience no longer sees theater as a rare opportunity to hear instruments, ooh instruments!).

Now, reviewing the first halves of our two plays again, we see a critical difference: Pericles is so full of plot it has no room for lazzi. Even though the text is actually slightly shorter, every single scene is either dramatic action, characters summarizing past dramatic action, or characters lamenting or planning new dramatic action. Non-dialog sequences would have been filled with the storm, and the mock combat. Famine and assassins do not give good openings for squeaky chairs and slurpy noodles. Meanwhile, the “nothing” that is going on in Love’s Labour’s Lost is a beautifully crafted skeleton designed for the addition of lazzi and comparable bits of comic “business.” Viewed from the plot perspective it’s Pericles where lots is going on and Love’s Labour’s Lost nothing, but if you instead summarize the comic business, the structural elements of a comic play, it’s Pericles where nothing is happening, while Love’s Labour’s Lost is packed with business of the best sort.

Let us take, for example, the midpoint scene which is the climax of many productions of Love’s Labour’s Lost—Act IV scene III, in which the four ridiculous gentlemen will at last decide to break their silly oath. Instead of anything straightforward, Shakespeare crafts a triple-nested eavesdropping scene, the eavesdropper being a theater trick as old as the messenger gag, and more versatile since it works in comedy and tragedy alike. Here Biron—the wittiest lord—overhears the King confessing his love. Then Longaville enters and confesses his love while both Biron and the King eavesdrop. Last Dumain enters and confesses his love while all three eavesdrop. Then Longaville reveals himself and chides Dumain for oathbreaking, the King then chides Longaville for hypocritically chiding Dumain, then Biron chides all three for their hypocrisy, and last a letter arrives revealing Biron’s love (sent by our anti-flirtation crimefighting team!). United in love and hypocrisy, the four finally “resolve to woo these girls of France.”

The dialog sparkles, but what truly makes the scene soar is the opportunity for ridiculous antics as one, then two, then three men try to hide themselves behind more and more implausible cover on an increasingly crowded stage. Every production has its own creative options: hide up a tree, up a ladder, under a desk, behind an urn, behind an audience member, curl up imitating a rock in pantomime… the options are as endless as the troops ingenuity. The king says when he enters “I have been closely shrouded in this bush!” but even that opens infinite opportunities: an unreasonably small shrub, a small potted desk fern, a twig…

In addition to hiding they can move about, try to avoid each other, making more ridiculous gestures and actions as they try desperately to be quiet. The text says that the king drops his love letter on the ground: in what hilarious attempting-to-be-silent way will he try to retrieve it before Longaville finds it?

Even if it isn’t strung out at great length, Biron hiding gives the actor the opportunity to perform the lazzo of climbing a ladder in a silly way, and in productions like the Globe’s (highly recommended!) it can be quick but still highlight enough to make the audience burst into applause. Twice. And the rest of the first half of Love’s Labour’s Lost is full of similar opportunities. The comic potential is actually enhanced by the fact that nothing is happening, since we know it doesn’t matter if our attention strays from the “plot” to a secondary character wriggling about in the background.

“What!” you may object, “but Love’s Labour’s Lost has some of Shakespeare’s most gorgeous and elaborate sonnets, puns and puzzle-box-tight language! How can you say we aren’t supposed to be paying attention to it?!” It does, and it’s true, and much of the humor in Love’s Labour’s Lost comes from its quick, intricate jabs and brilliant application of the word Honorificabilitudinitatibus (which has a leg up on Supercalifragilisticexpialidocious because it’s a real word!). Yet the heart of the play is how Shakespeare allows for the symbiosis of excellent dialog with excellent opportunities for comic business, and if you doubt that then watch the Globe production and then the BBC Shakespeare Collection version (performed in traditional dry style with minimal improv) and count how many times you laugh.

It is important to acknowledge, in this comparison, that Pericles Prince of Tyre is a comedy in a different sense from Love’s Labour’s Lost. If Love’s Labour’s Lost is a comedy like Plautus, intended to make us laugh, Pericles is a comedy like Dante, intended to show us a moral story with a happy ending, where fate punishes the wicked and virtue carries the good people forward through trials to their just reward. The adventures and moral lessons Pericles packs into the first half aim to be exciting (and instructive) in themselves, and the lack of space for lazzi type improvisation is intentional. Intentional, yet not necessarily successful, since the jam-packed opening section is so indeed dramatic, but not as dramatic as a full-on drama, largely because there is so much so fast that it’s hard for the audience to grab on to any given piece. The story is trying hard to show that Fate is complex, rewarding vice and virtue in ways we can’t understand until the end, but the events feel so (intentionally) arbitrary that, even in a very good production, they have trouble feeling real. As a friend said when we watched it together: “Pericles has too many things. None of them matter.” While harsh, that is the feeling I tend to have while watching Pericles: detachment from the importance of any given event. This is not inherent in stories about the overheavy hand of fate—think of Candide—but it is a strongly present feeling even in very good presentations of Pericles Prince of Tyre. Meanwhile Love’s Labour’s Lost has nothing going on, so the audience can revel in the pure art.

Returning to our plots, both plays undergo massive changes at the midpoint.

Here Pericles changes authors and becomes real Shakespeare, and we can feel it instantly. Plot summary, part 2:

Princess Marina has become the most beautiful and outstanding maiden Tarsus, so the other princess (heiress of the kingdom) is totally ignored. Jealous, the queen who raised both girls orders a servant to murder Marina. Waffling because of her virtue and persuasiveness, the assassin is interrupted by the famous Spanish pirate Valdes! (What century is this again?) who carries Marina off into slavery. Pericles returns to Tarsus (why now after almost twenty years?) to reclaim Marina, but is told that she died. Meanwhile, Marina is sold to a brothel in Mytilene (kingdom #5) where the pimps expect big profits, but she is so virtuous (and dedicated to her chastity) that she keeps persuading prospective customers to repent and swear off going to brothels forever. She pulls this on their most important customer, Lysimachus, the governor of Mytilene, who is impressed and tries to help her (by giving her money, not by rescuing her from the brothel). The pimps decide the only way to break Marina’s spirit is to rape her, but she persuades them to instead let her set up as a schoolmistress teaching music, literature, handicrafts and other virtuous arts, and giving the profits to the pimps. Some time later, a ship brings Pericles to Mytilene (why?), but he has gone mad with grief and just sits, refusing to speak to anyone. Governor Lysimachus brings Marina to cheer up the mysterious stranger, and she tells him her backstory (which she hasn’t told to anyone in Mytilene?) and he realizes she is his daughter. The reunion cures his madness and all are happy, and Lysimachus and Marina decide to wed. Then Pericles has a vision in which the goddess Diana tells him to go to her temple at Ephesus (archaeologist recommended!) where the long lost queen is found, the family reunited, and the gods are much praised for rewarding virtue.

Shakespeare’s hand is not just in the beauty of the dialog. The plot has also decelerated, making space for humor as well as for deeper drama. We also see Shakespeare’s hand in the sudden return of more classical theatrical elements. Shakespeare knew his Plautus as well as any classicist, and the second half of Pericles parodies and critiques one of the most ubiquitous and implausible aspects of classical comedy: the inexplicably virgin prostitute. Those who have seen Plautus or Terence (or A Funny Thing Happened on the Way to the Forum) know this bit: the long lost daughter of Nobleman X has been sold into slavery and is in a brothel conveniently next to the home of Aristocratic Youth Y, who falls in love with the beautiful courtesan. Hilarity ensues culminating in their marriage, enabled by the revelation that she is (A) freeborn, (B) noble, and (C) still a virgin despite having been in a brothel for many years?! Plautus gives no explanation, and it gets less plausible the more research we do on the history of slavery and sexuality in antiquity (good sources here and here). Shakespeare and his audiences, who have sat through Plautus and possibly even Terence thanks to Renaissance humanist enthusiasm, are aware of how ancient playwrights willfully ignore this issue, so Shakespeare takes up the familiar trope and ornaments it. Just as his eavesdropping scene is triple-nested, his implausibly virginal courtesan is a font of speeches about piety, nobility and chastity, which, depending on the director, can feel like an incredibly powerful female voice, or be presented as over-the-top satire, either of which is powerful, and extra powerful for audiences familiar with this cliché. The deus ex machina ending of Diana’s vision also works, and defuses some of the implausibility of earlier sections by having the gods be as heavy handed in solving Pericles’ woes as they were in shaping them, and does its best to transform the play’s implausible mountain of events from a bug into a feature. It works. And here and there Shakespeare throws in bits where one could insert lazzi type improvisation; played very, very carefully even the wrestling between the girl and the pimp in the attempted rape scene can be turned into physical comedy which helps defuse the threat of sexual violence and set the modern audience at ease.

But let’s see how well this stands up against what Love’s Labour’s Lost has to offer. What do you say, gentlemen? Ready yet to woo these girls of France?

It is at the crux, after Act IV, that Shakespeare makes his most brilliant move: he lowers the stakes. The lovers are all successfully in love. The only impediment between everyone and a happy ending filled with weddings was the king’s silly oath, which he has resolved to break. The tension is over. If there was nothing going on in the first half of the play, that nothing has been resolved. There is now less than nothing going on. Even the most vacuous skeleton of plot has neatly wrapped up by the middle of the play. Shakespeare cracks his knuckles. He will now keep us in our seats another hour while literally nothing happens. (It feels worth mentioning that at this point I went to my DVD to check one detail in the next scene, and ended up watching through to the end because Shakespeare is just that good at writing nothing!)

I cannot supply a plot summary here. There is no plot. In first scene loooooong scene, packed with bad Latin, grammar jokes and insult games, the only “plot” is that the “fantastical Spaniard” asks the priest and schoolmaster to help him improvise some kind of show to entertain the princess. That isn’t a plot, it’s killing time by having actors discuss how they’re going to come up with a way to kill more time! There’s even a character who watches silently through the whole thing, serving only as someone others make incomprehensible puns at, so at the end when they comment “Thou hast spoken no word all this while,” he can reply deadpan, “Nor understood none neither, sir.” It’s a hilarious moment (and a great example of how silent observer characters can be hilarious on stage but invisible in text), but, still, nothing happened in that scene! Nothing! In the next scene the four gentlemen come to woo the ladies while dressed up as Russians for no reason! We don’t even get a scene of them coming up with this idea and explaining why, Shakespeare just plunges in knowing we will be absolutely delighted to see the king and lords being teased mercilessly while they fail utterly at passing for ridiculous Russians! (The girls disguise themselves too, just for giggles).

What next? The men take off come back not in disguise and get mocked some more. Then things seem to be starting to happen, but interrupt each other so nothing can. The other characters interrupt the mocking with their diversion: a terrible play about the Nine Worthies, which the gentlemen interrupt all the time by mocking it. Then the interruptions of the play-within-a-play time-killer are themselves interrupted when the rustic man accuses the Spaniard out of nowhere of having gotten the wench pregnant, and what looks like it might be a duel, or a fist fight, or at least a brawl of some kind degenerates into wild interruptions and hooliganism without even a coherent fight. Every production of Love’s Labour’s Lost adds different comic “business” to these scenes, from song and dance (as in Brannaugh’s, above) to brawling and food fights (as in the Globe), to whatever this is:

The audience is rolling in the isles. And then the comedy comes to a screeching halt when a messenger arrives to tell the princess that her father, the King of France, is dead. The mirth stops. All the interruptions are interrupted by the intrusion of the first thing which has happened all play which one could normally call “plot,” the death of a king. Except it’s the wrong plot, the wrong thing for a plotless comedy, and the theatrical whiplash is stunning. Shakespeare has not only made us sit here an hour watching characters kill time by talking about killing time, he has made us angry when something did actually happen. We protest: “Will, you jerk! We don’t want plot; we want our nothing back!” And for the first time we realize how much we really were enjoying a play about less than nothing.

Shakespeare sticks hard to his betrayal of the comedy contract. We will have no wedding at the end. Instead, in a twist of jarring reasonableness, the ladies say they will not trust the vows of lifelong love made by oathbreaking suitors who just met them yesterday, and demand that the men take on difficult tasks for a year and then return if they still love them after that. It’s powerful, it’s sincere, it’s a deep jab at the entire genre by criticizing rash love at first sight as unreliable and unsustainable (pro tip for Juliet), and by twisting the usual power dynamic of lady and suitor by making the marriages not about dowry and politics (like real Renaissance weddings) nor about rash love (like comedy weddings), but about proving the possibility of serious, sustained relationships.

But while he betrays all the plot elements of the play—much as he has been doing the whole time by having no plot, and then less plot—Shakespeare still sticks to the structural promise of the play, that it will provide an ongoing framework for improvisation and extra entertainment. Most summaries say the play “ends” when the news arrives and the women tell their suitors to seek them again in a year, but after that the silly Spaniard returns to deliver—in the midst of grief and tested love—the immortal line: “Will you hear the dialogue that the two learned men have compiled in praise of the owl and the cuckoo? It should have followed in the end of our show.” And on this little hook, Shakespeare hangs one last crowd-pleaser, a nice finale song, which is an allegory about how time-tempered love is more reliable than rash quick love, but is also a satisfaction to the little voice in the back of the viewer’s mind which has been whining, “I want my vacuous entertainment back!” And, irrelevant as it feels in text, the song is a pleasing, almost soothing finale in a performance, by massaging away the sense of betrayal while preserving all the strength of the comedy meta-commentary Shakespeare has just achieved.

Structure, rather than line-by-line success, is what I hoped to get at in this rather unfair comparison between one of Shakespeare’s best-written and most popular plays and one that is half neglected, and also only half his. As I tried to demonstrate in my dips into Plautus and Commedia dell’ Arte, “Plot” is only one way of outlining the components that fill up a story’s word count, or scene count. We talk a lot about character arcs or plot threads, but, just like a rock that looks like a face from one side but something else from another, so sometimes what is going on at the heart of a scene might be completely orthogonal to any plot event you can describe in it: an eavesdropping scene, a moral lesson, a man making us love watching him come down a ladder. A message can be delivered in a single sentence or an endless scene.

In these plays, the incestuous King of Antioch and the distant King of France both die suddenly off-stage, a traditional shortcut and often (though not always) a sign of bad writing. And both deaths serve, from a plot perspective, to make the connected character return home, Pericles in one case and the French Princess in the other. But both are also the death of a structural thread. The death of the King of Antioch is the death of Pericles’ entire motivation for traveling, and in many ways the death of the audience’s willingness to accept that this journey makes any sense, so everything thereafter happens for no particular reason. It is the death of credibility, and the transition to the absurd. The death of the King of France is the opposite, since everything until that point had happened for no particular reason. It is the death of the entire comic contract, the whole promise of the play, except for finale music to give the audience one last smile. Both deaths, in a plot synopsis, feel the same, but if we rotate our angle and outline, not by plot, but by scene, by hook, by lazzo, by narrative promise, the new outline is just as valuable.

This is not unfamiliar; we do this kind of analysis every time we see a familiar tale like Sleeping Beauty retold to be five hundred words in one adaptation and five hundred thousand in another. Plays are a particularly easy demonstration of this since so much of their content is invisible in the script (from silent eavesdroppers to physical comedy), challenging us to compare the skeleton of a Commedia script which can pack a half hour scene into 100 words to something as wordy as Shakespeare. But I hope this whole comparison will help us remind ourselves that we can compare apples to oranges, can compare Love’s Labour’s Lost to Pericles Prince of Tyre, the plotless with the over-plotted, and that exciting insights await when twist things around and compare them sideways, structure to structure instead of plot to plot.

Shakespeare would have me finish on a song, but hopefully we can modernize and finish on a comment thread.

Ada Palmer is an historian, who studies primarily the Renaissance, Italy, and the history of philosophy, heresy and freethought. She also studies manga, anime and Japanese pop culture, and has consulted for numerous anime/manga publishers. She writes the blog ExUrbe.com, and composes SF & Mythology-themed music for the a cappella group Sassafrass. Her first novel is forthcoming from Tor in 2015.